Metals in exchange for security: What resources caught Trump's attention, and what can Ukraine offer?

A global competition is unfolding for rare metals, encompassing dozens of elements from the periodic table that underpin technological advancement worldwide.

The ambitions of major powers are growing faster than the development of new deposits. The U.S. aims to lead in artificial intelligence and semiconductors, the EU is focused on "greening" energy and transitioning to electric vehicles, while China seeks technological independence in key industries and aims to maintain its status as the world’s factory.

In the race for resources, major powers impose tariffs on each other and seek suppliers of rare metals, the reserves of which are scattered across the globe. For years, Ukraine has been trying to insert itself into this competition and become a source of valuable resources for Western partners looking to reduce their reliance on Chinese raw materials.

The domestic deposits of metals represent a story of unrealized potential. Currently, this resource has caught the attention of the U.S. president, who sees it as an opportunity to "pay" for American aid. Ukraine, on the other hand, aims to utilize this raw material to attract private Western investments and secure guarantees of safety.

Why These Metals Are Essential

Certain metals are critical for technological progress. For instance, lithium, cobalt, and manganese are used in battery production, silicon and gallium are essential for semiconductors, titanium and aluminum are used for aircraft fuselages, while rare earth metals are integral to most household appliances.

7

7However, the supply chains for these raw materials are unstable. The extraction and processing of metals are spread across the globe, particularly in quite volatile regions. For example, 70% of cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), 20% of manganese comes from Gabon, and 15% of uranium is sourced from Namibia and Niger.

Another factor contributing to instability is China, which invested heavily in the extraction and processing of critical raw materials in the past, gaining a monopoly in the market, and is now using it for political purposes.

China wields its monopoly as a weapon in trade wars with the U.S. and EU. In 2023, the Chinese authorities banned the export of technologies for processing rare earth metals and restricted the export of graphite; in 2024, they limited the sale of antimony, gallium, germanium, and intensified oversight of processing companies.

In 2025, Beijing implemented export controls on tungsten, indium, bismuth, tellurium, and molybdenum. The authorities plan to prohibit the export of technologies for processing lithium and gallium. These restrictions pose a threat not only to the economies of Western nations but also to their national security, as technological weapons are also produced from these metals. Some alloys can only be manufactured in China.

In recent years, the U.S. and EU have attempted to build reserves of strategic raw materials and diversify supply channels to reduce dependence on Beijing. However, finding non-Chinese sources of rare earth elements is challenging. Since 2018, the U.S. has increased its share of global extraction of such raw materials from 9% to 12%. China's share still stands at 68%, and in processing it is as high as 90%.

Strategic metals are not actually that rare. Explored reserves exist in many countries. For example, Brazil and Vietnam have rare earth metal deposits comparable to those in China, but their extraction is limited. Bolivia possesses some of the largest lithium reserves in the world, yet the country exports almost none.

Challenges arise at the stage of turning a metal source into a profitable business project. Mining companies struggle to establish raw material extraction, processing, and logistics, as well as to communicate effectively with local regulators.

For an investor, a country must be politically predictable, safe, bureaucratically clear, have infrastructure, and be close to the market. If these conditions are lacking, investors will seek more favorable jurisdictions.

For instance, Greenland has large reserves of rare earth metals, but investors cannot establish competitive deposits there due to a lack of roads and maritime routes. The island's authorities have even revoked licenses from some companies because they failed to commence full-scale extraction.

In the realm of strategic raw materials, there is increasingly more politics and less economy, and metal prices are gradually rising. Consequently, countries with imperfect investment climates and infrastructure are enhancing their chances of attracting significant foreign investments for the development of their own deposits.

Ukraine also aims to benefit from the fierce demand and disputes among major powers. It offers deposits that rank among the largest in Europe.

What Ukraine Has in Its Land

Ukraine presents valuable mineral resources to the U.S. for the aerospace, military, electronics, nuclear, and chemical industries. What minerals does the country possess?

8

8  9

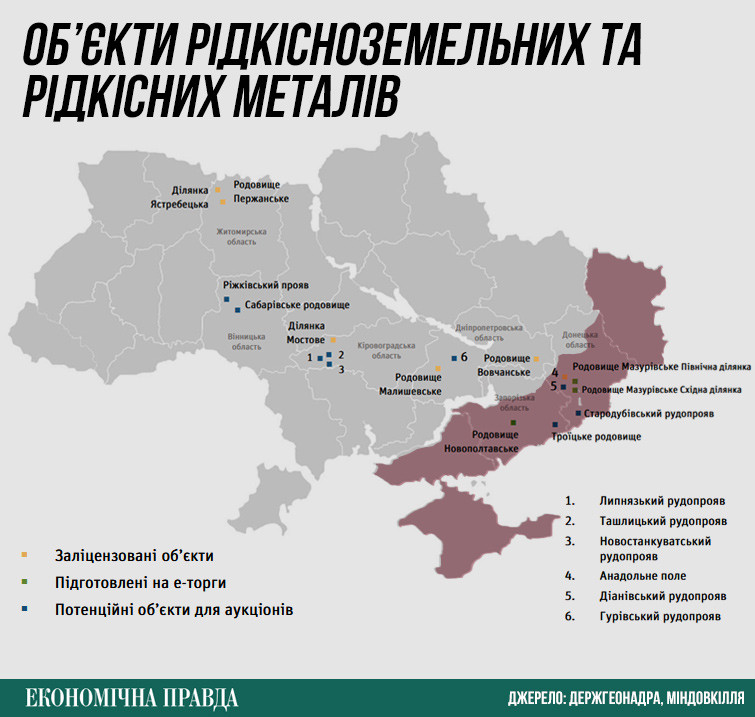

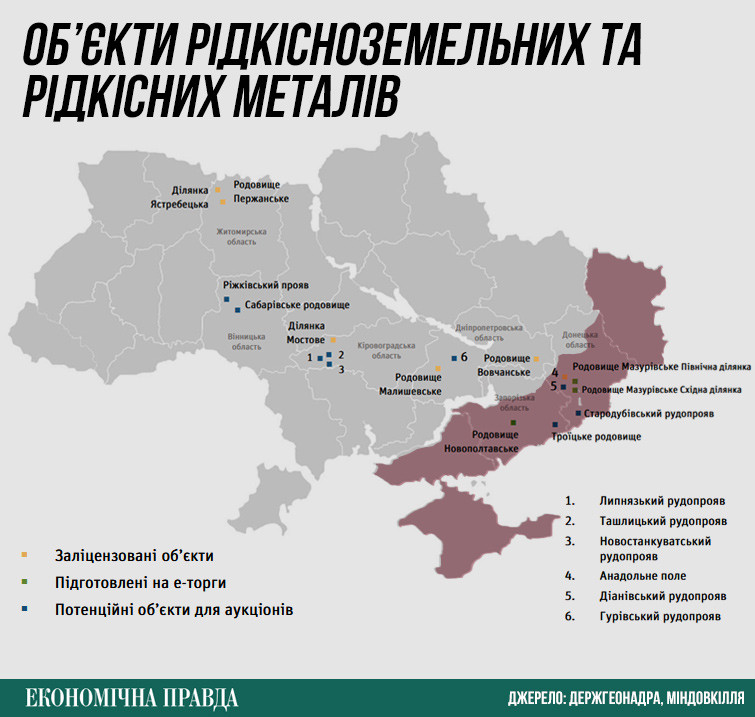

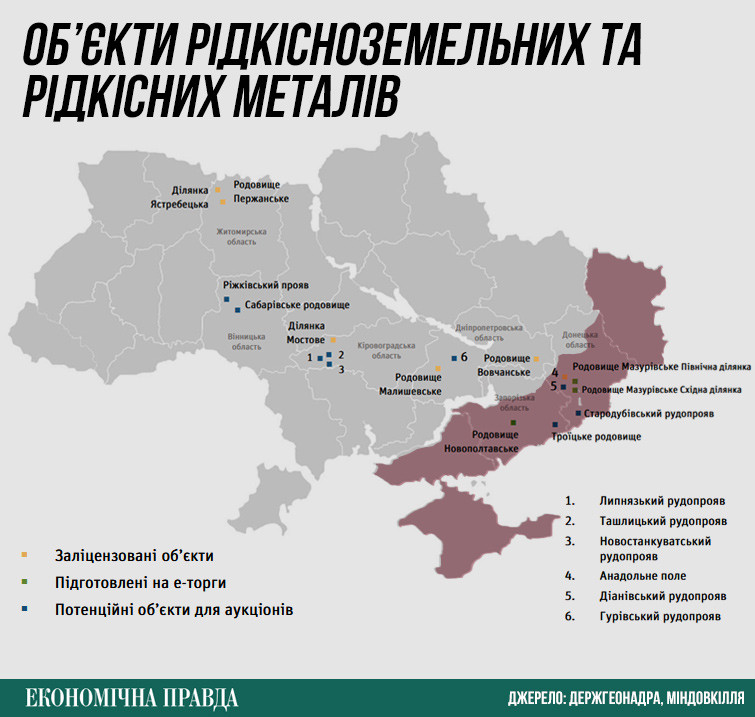

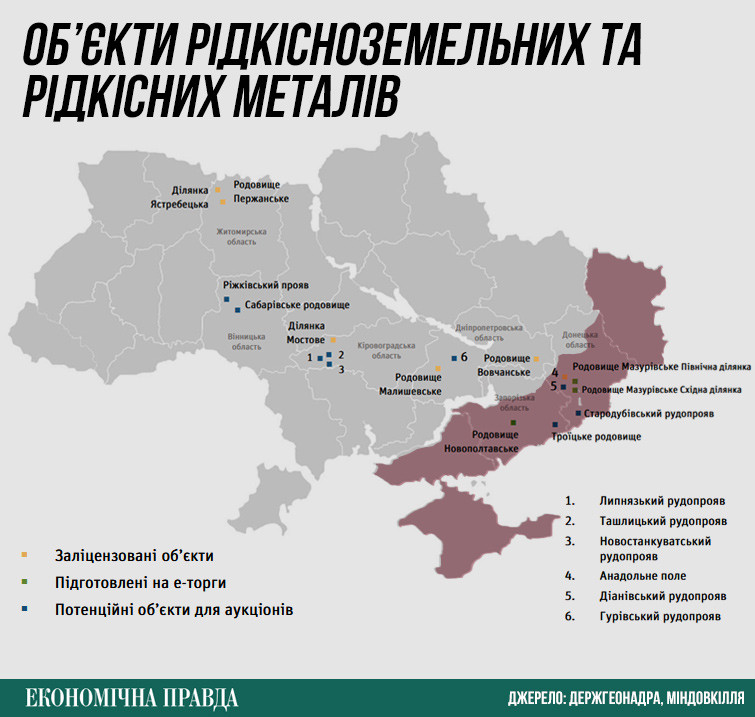

9The entire list of critical minerals in the country was presented by the State Service of Geology and Mineral Resources in the "Mineral User Investment Atlas" before the major war. American partners are particularly interested in rare earth metals.

Reserves of tantalum pentoxide, niobium, and beryllium in Ukraine are accounted for across six comprehensive deposits. Tantalum and niobium are mined only in non-commercial volumes as by-products of titanium placers. The prospects for extracting rare earth metals are largely tied to the development of the Novopoltavskoye apatite ore deposit and several other ore occurrences.

Ukraine has one beryllium deposit with reserves of 13,900 tons and associated elements. In 2019, a special permit for it was granted to the Ukrainian company BGV Group, co-owned by ATB Corporation's Gennady Butkevich and his partners.

0

0  1

1Lithium

Currently, lithium is not being extracted in Ukraine, although its reserves amount to about one-third of the proven deposits in Europe and nearly 3% of the global total. Three explored deposits and one preliminarily studied area are known, along with several lithium ore occurrences. All reserves are found in hard rocks.

2

2  3

3Graphite

Ukraine ranks among the top five countries in the world for graphite reserves, with about 19 million tons. Currently, six deposits are known, with one of them being industrially exploited by the Australian company Volt Resources. The exploration of three deposits is conducted by BGV Group and the Turkish Onur Group. The remaining deposits and over ten promising occurrences are open for licensing.